Post COVID economics will be very challenging. Ninety years ago, in response to the Great Depression, Western governments started to take responsibility for economic management. Fifty years ago, Western governments stopped taking responsibility for the value of their own currency. This year, these same governments took unprecedented control over the lives of their citizens, apparently to save them from a pandemic – devastating economies in the process.

As individual citizens and businesses look toward a post COVID world, many are questioning what the economy will look like. Some extraordinarily rich men are suggesting that we are about to embark on a ‘great reset’. No doubt they will use their influence to try and make this happen. What seems to be lost in the discussion is that economics and people are inseparable. An economy is the ecosystem in which people live their lives, so when the economy suffers, people suffer. When the economy thrives, people thrive.

The starting point

Never have so many given up so much for so little.

Why say this? Because the losses have been astronomical, while the gains have been infinitesimal. As more is known about COVID19, the more it resembles the annual flu. Overall morbidity rates have not varied from the long-term average by a statistically significant amount, nor has the age profile of morbidity, with the elderly dying at higher rates than the young. It is true that many people have died with COVID, it is not true that many people have died from COVID. There is a significant difference between these two things. The initial threat of COVID to our health has turned out to be grossly exaggerated. This is something we should be rejoicing.

The cost of the response to COVID is already immense, but the real cost will not be known for many years to come. Health professionals are warning of an onset of deaths due to postponed diagnosis of preventable diseases. Economists are warning of long-term job losses and business failures, while education professionals are concerned about the long-term impact of the ‘hole’ in learning and development created by school closures. While all these things are major concerns, there is also a very long list of other concerns that are more difficult to quantify including mental health, social cohesion, erosion of human rights and distrust in government.

At the same time governments have never been more indebted in peace time. This is even before any attempt is made to dig the economy out of the COVID-shaped hole that the governments have now created.

The options

Because governments have caused the economic devastation, people and businesses expect them to fix it. There are two popular suggestions for doing so, both based on Keynesian Economics. Keynesian Economics suggests that if governments invest heavily during economic downturns this will stimulate economic growth. The variations come from how that investment is funded. Modern Monetary Theorists suggest that government simply creates money via the Treasury (quantitative easing), without the traditional acknowledgement of that debt against the government. The second variation is very similar except that the debt is acknowledged and expected to be paid back to the Treasury by future tax payers (or through quantitative tightening). In theory, the implications of these options on individuals are opposite. Modern Monetary Theory is likely to lead to rampant inflation, while a heavily taxed society is likely to result in deflation.

In practice, recent history suggests that it is not how the money is sourced, but where it is spent that makes the most difference. During the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), different countries adopted different strategies to try and stimulate recovery. The USA introduced an unprecedented level of quantitative easing, while the European Union initially opted for austerity measures. In both cases these measures were applied from the top down through the banking and finance system. At the same time Australia made payments directly to individuals in the lower socio-economic bracket as well as bringing forward micro-investment programs in government infrastructure (e.g. school buildings).

In theory the top-down approach gets a better bang for buck, as the banking system multiplies the investment many times over as it distributes it in the form of loans. Whereas there is no multiple on the direct investment to individuals. In practice the direct investment was far more effective, Australia was the only one of the 20 largest Western economies to avoid a recession and went on to record the longest run of uninterrupted growth in the world – from 1991 to early 2020.

So why did the Australian method work, and the others fail? First it is important to understand that money is a catalyst to trade. Catalysts make transactions easier without actually being affected by them. When there is a lack of catalyst, adding more will facilitate more transactions; when there is an abundance of catalyst, adding more will make no difference. The reason that adding more money into the top of the finance system made no difference was because there was already an abundance of it. This is evident in the record levels of World debt, so adding more debt to this (via quantitative easing) simply increased the level of excess – that it is in excess is also evident in the record low interest rates. The Australian method was to add a catalyst to facilitate transactions that would otherwise not have occurred – so it worked.

So, your government has a choice to make and the impact of that choice will have a profound impact on what sort of economy you need to plan for.

One – Traditionally Funded, Top Down Financing

This was the approach taken by the European Union in response to the GFC. It is the accounting response to a business problem, rather than a government response to a social problem. The implications for you if your government chooses this path is higher taxes – probably on property, lower growth, and higher unemployment and the social unrest that usually accompanies this combination.

Two – Traditionally Funded, Bottom Up Financing

This was the approach taken by Australia in response to the GFC. It is a targeted government response that will result in winners and losers. On one hand the government gives away money to individuals, on the other it will need to increase taxes to pay for this. The implications for you if your government chooses this path depends on whether you’re a chosen beneficiary, or one of those that will be paying more taxes. This contrast is politically sensitive. However, to have the most impact, the funding should be directed to those who need it most. Also, the increased tax burden can be delayed reducing the resentment of those who will eventually be paying for the spending.

Three – Treasury Funded, Top Down Financing

This was the approach taken by the USA in response to the GFC. It is the banking response to a financial problem, rather than a government response to a social problem. The implications for you if your government chooses this path is higher government debt, lower interest rates, asset inflation (property and shares) and increased divide between rich and poor.

Four – Treasury Funded, Bottom Up Financing

This approach is only available to governments that have their own currency, so State and local governments cannot use it, nor can countries within the EU. This approach was successfully taken by Germany in the 1930’s, an extreme version of it is supported by those in favour of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). The bankers and accountants are opposed to MMT because they see it resulting in hyperinflation – where the value of money declines rapidly. Hyperinflation has occurred several times in history, most famously in Germany in the 1920’s, and most recently in Zimbabwe. However, as Germany showed in the 1930’s, hyperinflation is not a guaranteed outcome of Treasury funded bottom up financing. Many countries have already started down this path in response to COVID, drawing on Treasury funding to provide compensation payments to individuals and businesses worst hit by the lock downs.

The implications for you if your government chooses this path depends on the extent of the program. Floating currencies mean that money is only worth what everyone believe it is – and this can have serious consequences. So governments need to balance the benefits of using Treasury funding against undermining belief in the value of the currency. Providing they can achieve this balance it will allow them to increase the number of beneficiaries and the size of the funding provided to them, without needing to burden other individuals and business with higher taxes. However, if this gets out of balance, inflation is likely to accelerate rapidly. With the value of money at risk, the most vulnerable individuals and businesses will be those paid in arrears (including many businesses), on fixed income or living off their savings.

Five – Treasury Funded Debt write-off

This approach is only available to governments that have their own currency, so State and local governments cannot use it, nor can countries within the EU. This approach is different to the debt defaults of late last century (often associated with Latin America). The key difference is that government buys back the debt using Treasury funding, then Treasury absorbs the debt. It has a similar underlying principal to MMT in that Treasury funding is treated as unlimited. The difference is that it is a one-off write-off of the debt which prevents the government from having access to unlimited funds that are likely to lead to government excess and overreach. It is also an option for which strict conditions can be put in place – for example in a democracy a referendum may be required, and there may be strict limits on how often referendums can be taken, such as once only during the reign of a particular government. This can also be used to introduce strict limits on government overspend, perhaps triggering an election if these limits are reached. The implications for you should your government choose this path, is that you would be required to support it and the associated changes to your Constitution. If done clearly and transparently it is the best option, but the devil is in the detail, so be careful of the fine print.

What is most likely to happen

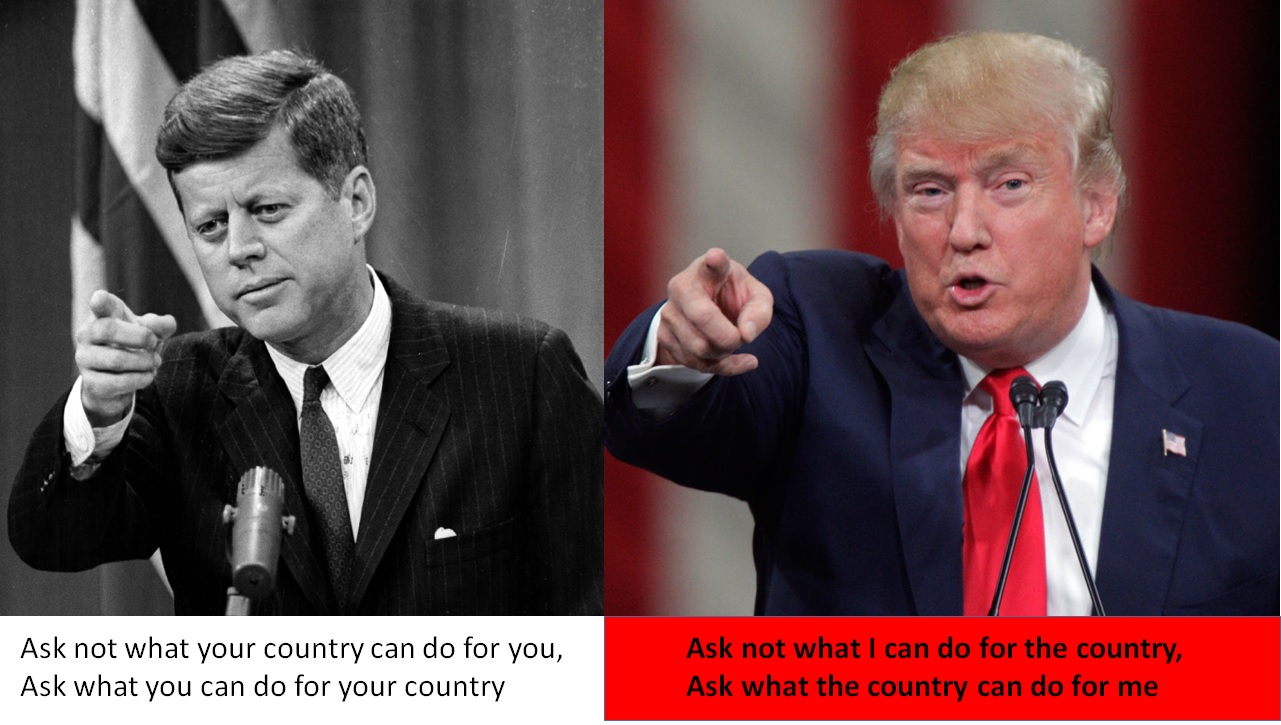

Given the starting point and the size of the problem, the most likely scenario for countries that control their own currency is Treasury funded bottom up financing. The concern with this is that it provides the government with a great deal of power over their citizens as it flips the balance from the government being dependent on its citizens for income, to citizens being dependent on the government for income. This can lead to government overreach.

There are already examples of this in many places throughout the world where people’s rights, freedoms and livelihoods have been devastated by draconian leaders in response to COVID. Many of these have abused emergency powers to override Constitutional constraints on their powers and the rights of their individual citizens. 1930’s Germany did not vote for Fascism, the existing Socialist government morphed into Fascism right before the German people’s eyes.

Totalitarian leaders need an enemy to justify their behaviour. Their preferred enemy is non-physical: Communism, Capitalism, religion, terrorism, a virus, conspiracy theorists, etc. Their goal is not to conquer the enemy, it is to gain the compliance of the people. Being in control of the money supply has always been a key component of power. You only get the money you need if…

Economics has never been less about money and more about people than it is right now.